Recently, images of air tankers releasing bright red and pink powder over Los Angeles suburbs have taken the internet by storm.

The dramatic, almost surreal sight has a practical purpose as the Forest Service uses fire retardants to help fight the raging wildfires. These substances coat vegetation and surfaces to starve the fire of oxygen, slow the burn and give ground crews a fighting chance.

The vibrant colours serve another purpose too—helping pilots see where they’ve already dropped the retardant, ensuring efficient coverage without overlap. Ground crews use the bright lines as markers, staying behind the treated areas where the fire’s intensity has been reduced.

But here’s the thing: While these chemical suppressants might help fight fires, they’re not without their downsides. Recent research suggests they can be harmful to both human health and the environment. The chemicals in fire retardants pose risks to fish, wildlife and sensitive ecosystems, prompting the Forest Service to restrict their use near waterways and habitats of endangered species—except when human lives or public safety are at risk.

This got me thinking about my own little corner of the world, far from California’s flaming hillsides but not immune to the ripple effects of our environmental missteps.

Closer to home in Ontario, the threat of forest fires looms large during peak season.

But, they aren’t just a symptom of climate change, they’re also the result of long-standing practices that ignore the wisdom of natural systems.

If we take a moment to listen to the lessons these disasters are teaching us, we can shift toward a more balanced, sustainable approach to forest management here in Ontario.

The Kenora 51 wildfire burned in northwestern Ontario as thousands were evacuated from five First Nations due to conditions. The Kenora 51 wildfire, which ignited on June 8, 2021 became one of the largest wildfires in the province's history, consuming more than 200,000 hectares of forested land.

The problem with monocultures

Imagine walking through a forest of trees all planted in straight rows, all the same species and the same age. To the untrained eye, it might seem like an orderly, well-maintained forest. But in reality, monocultures like this are an ecological disaster waiting to happen.

Monocultures are highly vulnerable to pests and diseases. When one species dominates, a single pest can wipe out the entire population, as we’ve seen with bark beetles devastating California’s pine forests.

Closer to home, the Emerald Ash Borer has left countless ash trees in Simcoe County, including my own, standing as dried-out hazards. With rising temperatures fueling its spread, the insect has surged northward, now ravaging ash trees in the Greater Sudbury Area.

The glyphosate gamble

Another practice contributing to forest fires is the widespread use of glyphosate, a herbicide sprayed to kill undergrowth. The logic seems sound: clearing out the underbrush reduces the amount of fuel on the forest floor. But here’s the kicker—glyphosate also kills native plants that help retain moisture in the soil. What’s left is a dry, barren landscape, practically begging for a spark.

When native species like birch, aspen, and fireweed start regrowing in a clear-cut forest, they’re treated as competition for the conifers prized by the timber industry. Glyphosate clears them out, creating a tree-farm monoculture.

While this might make sense financially, it’s a disaster for ecosystems. These monocultures are less hospitable to wildlife, insects, and fungi. They’re also more flammable.

Let’s pause for a moment.

Glyphosate isn’t some benign garden helper. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified glyphosate as “probably carcinogenic to humans.” Since then, thousands of lawsuits have been filed against these chemical companies with settlements nearing $11 billion.

Yet, somehow, it’s sprayed over Canadian forests to kill native plants deemed inconvenient for logging companies, as forestry policy still primarily prioritizes the timber supply—resulting in thousands of hectares of Crown land being sacrificed.

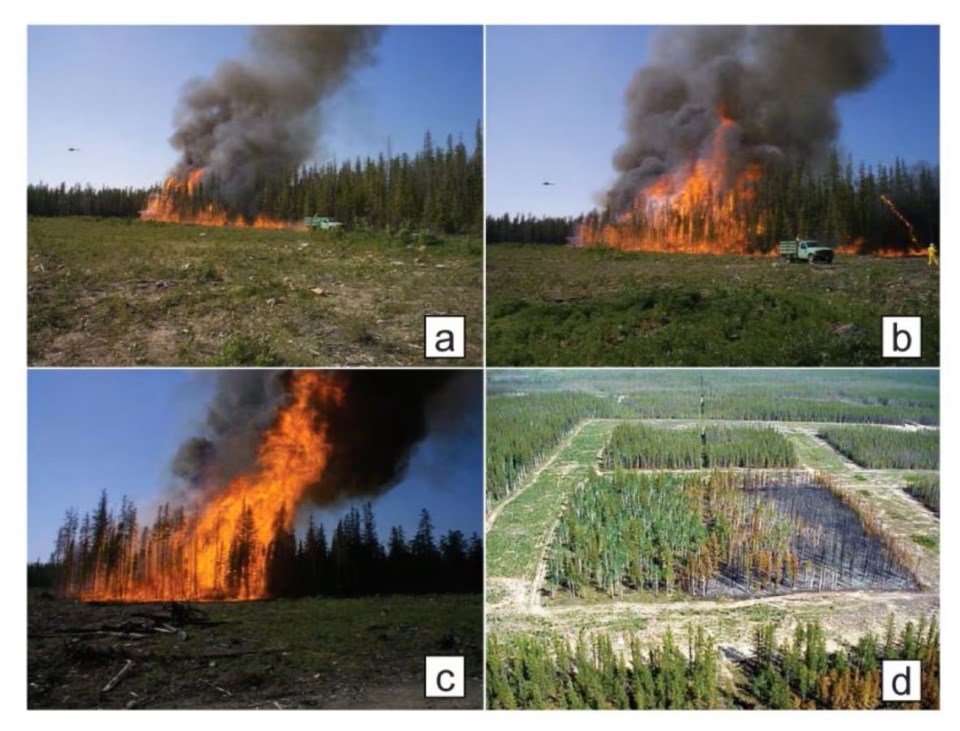

A test burn conducted by a federal fire behaviour specialist shows, at bottom right, how aspen can resist a wildfire spreading through jack pine and black spruce. (The Forestry Chronicle photo)

A test burn conducted by a federal fire behaviour specialist shows, at bottom right, how aspen can resist a wildfire spreading through jack pine and black spruce. (The Forestry Chronicle photo)

This isn’t just a theory—it’s playing out in real-time. The fires have emitted more carbon than entire countries do in a year, and the cost—human, ecological and financial—is staggering.

The irony? The very forests being sprayed with glyphosate to protect timber yields are becoming tinderboxes. It’s a vicious cycle, and it’s one we urgently need to break.

A healthy forest is a diverse forest. Instead of replanting cut-blocks with a single species of conifer, we should aim for a mosaic of trees, shrubs and understory plants that mimic natural ecosystems.

Forest management shouldn’t be left to corporations and government agencies alone. Local communities, Indigenous leaders and environmental advocates must have a seat at the table.

The ripple effect of glyphosate

When glyphosate rains down from planes, it doesn’t just kill plants—it changes everything.

Those broad-leaf trees aren’t just weeds; they’re life support systems for the forest. Moose munch on their leaves, birds nest in their branches and their fallen foliage enriches the soil.

Without these trees, wildlife struggles.

Studies near Thunder Bay show moose populations dropping in glyphosate-treated areas because there’s less food. And it doesn’t stop with the animals. Glyphosate lingers in the soil, messing with microbial communities that keep plants healthy and productive.

And here’s the thing: Traces of glyphosate have been found in wild berries and medicinal plants that First Nations' communities rely on. Imagine heading out to forage for food or medicine, only to find they’re contaminated with chemicals. It’s heartbreaking and infuriating—and it’s a violation of Treaty rights.

The bigger picture

The use of glyphosate in Canada’s forests is part of a larger problem with timber supply prioritized over ecosystem health.

Canada is one of the world’s largest producers of softwood lumber, with exports valued at more than $22 billion annually. Legislation often protects this revenue stream at the expense of biodiversity, water quality and fire resilience.

But the tide is turning.

In Quebec, glyphosate was already banned in 2001, shame on us!

Next week, Ecojustice lawyers, representing Friends of the Earth Canada, the David Suzuki Foundation, Safe Food Matters and Environmental Defence Canada, will be in federal court to challenge Health Canada’s renewal of pesticide products containing glyphosate.

This legal battle is more than just a fight against a chemical—it’s a call to reassess how we manage our forests and protect biodiversity for future generations.

We have the tools to make a difference: Science, traditional knowledge and the voices of advocates demanding change. It’s time to act before our forests—and the ecosystems they sustain—become another casualty of shortsighted management.

Monika Rekola is a certified landscape designer and horticulturist, passionate about gardening, sustainable living and the great outdoors. Contact her at [email protected].