It was a watershed moment of sorts for Ted Nolan.

During an interview about truth and reconciliation with TSN three years ago, the former National Hockey League coach of the year began speaking his truth about the racism that had dogged him from the time he was a junior hockey player all the way to his illustrious coaching career.

He suffered so many emotional breakdowns while recounting his experiences he could barely get through the interview, which would go on to form the basis for the 2021 documentary The Unwanted Visitor.

“All the past trauma issues that I went through came to the forefront,” Nolan said during a recent interview.

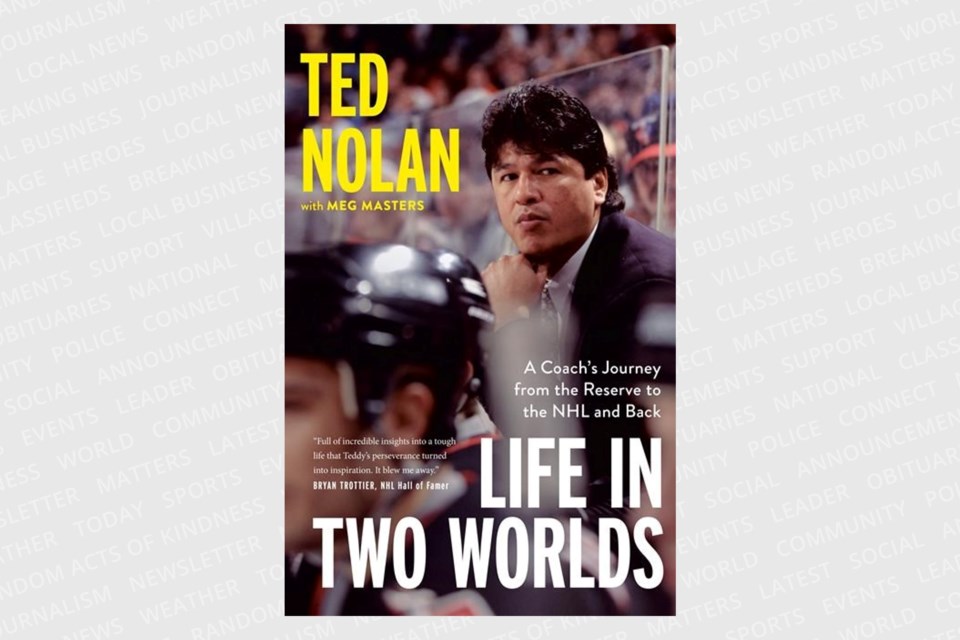

Nolan, who was born and raised in Garden River First Nation in a family of 12 children, delves even deeper into the racism he experienced in his recent book entitled Life in Two Worlds: A Coach's Journey from the Reserve to the NHL and Back.

Penguin Random House Canada reached out to Nolan following the airing of The Unwanted Visitor, with the idea of working on a book detailing his lived experiences with racism as an Anishinaabe person in the game of hockey.

“I didn’t plan on writing this book,” said Nolan. “The more they talked to me about it and what kind of things we would be discussing, I thought it would be a good thing — if you don’t talk, who knows?

“Hopefully, this can help the ones that follow.”

The beginning of Nolan’s hockey was fairly organic: he decided to make his own backyard rink as a youngster, only because the outdoor rink across the road from his home in Garden River was constantly being used by the adults.

That’s where Nolan’s love of hockey began; his father would place him in a recreational league in Sault Ste. Marie, where that passion for the sport really “took off” for him.

It wasn’t until he was 16 or 17 years old when it all “switched from really loving the game to trying to survive in the game,” as a junior player in Kenora, Ont. who happened to have long hair and “didn’t look like everyone else.”

It began in training camp with a couple of hockey players taking their sticks to his legs and cross checking him, and would eventually escalate with racial slurs being hurled at him and having to defend himself physically at a number of rinks in the area.

“I never fought in hockey until I went there, and that was just in training camp,” he said. “Then you go to rinks and you hear it from the fans in Kenora. Basically, the same thing happened at school.

“I just lost my father the year before I went up, and you just felt all alone — you know, a 16-year-old boy going through that stuff.”

Nolan would eventually make some friends and earn respect from others while in Kenora. But to this day, he doesn’t remember a single game he played — a symptom of blocking everything out and repressing his feelings in order to survive.

“To tell the truth, I don’t really know what made me stay,” he recalled. “I really wanted to fight, to show that we belonged in anything we chose to do — and by quitting, I always felt that you’re letting the bad guys win.”

Nolan eventually made it to the National Hockey League, lacing up for the Detroit Red Wings during the 1981-1982 season after spending a few seasons in the minors, where he experienced racism from fans, players and coaches alike.

When he was told he couldn’t play the game anymore after being injured as a member of the Pittsburgh Penguins, he said it was a “sigh of relief.”

“After every season, I couldn’t wait to get home because it’s kind of like you’re holding your breath the whole time you’re there, just trying to fight through and trying to survive,” he said.

Nolan would eventually begin coaching as an assistant with the Soo Greyhounds of the Ontario Hockey League at the request of Sault Ste. Marie hockey great Phil Esposito.

“That’s when I really found my true calling,” said Nolan.

After moving into the head coaching role, Nolan would lead the Greyhounds to the Memorial Cup championship in 1993.

Nolan went on to the National Hockey League (NHL), where he won the Jack Adams Award as coach of the year in 1997 for his role as head coach of the Buffalo Sabres.

But his relationship with the Sabres organization soon turned sour amid a number of rumours; Nolan said there was some buzz about him getting then-general manager John Muckler fired, that Nolan was drunk at practice, and that he had turned down a lucrative contract extension.

Nolan firmly believes that talk was fuelled by racism and discrimination.

“To win coach of the year in the National Hockey League, and all of a sudden you’re out of the league for 10 years — you know, something’s wrong with that,” he said.

Nolan returned to the NHL after his decade-long exodus from the league, coaching both the New York Islanders and Buffalo Sabres.

Would he still be coaching in the NHL if he were white?

“No question,” Nolan responded. “And I really strongly believe that it’s based on friendships and relationships and growing up in the same neighbourhood. When you grow up on one side of town, it’s hard.

“I was just very fortunate and very lucky that I was at the right place at the right time to become the coach of the Soo Greyhounds.”

Fast forward to the present day, and Nolan feels as though the sport of hockey has improved when it comes to accepting people from different walks of life. But that isn’t to say there aren’t barriers still in place.

“It’s getting better,” said Nolan. “But for any marginalized people or any low-income people, it seems not just to be discrimination and racism separating it, it’s the income that separates it — the financial means that you have to have to compete in this game.

“Young Ted Nolan would never make it now, because of the hockey schools, the sticks, the equipment, the specialized training, the elite programs.”

In 2013, Nolan helped develop 3 Nolans — a hockey school for youth in First Nations across Canada — with his sons, former professional hockey players Jordan and Brandon.

Nolan says the school is one of the greatest things he’s ever been associated with because he gets to go into First Nations and talk to kids not about making it to the NHL, but working towards their dreams in the general sense.

“We talk to kids certainly about the sport, but the sport is to get them there: then, we talk to them about the importance of education, nutrition, working and believing in yourself, and all the things that kids need to be inspired,” he said. “It’s definitely not to inspire them to be the next NHL player, because we all know how difficult that is.

“But if one or two do make it, then hey, that’s icing on the cake.”

Nolan doesn’t know how many copies of Life in Two Worlds have been sold or how his new book is faring at the moment.

But in an age where the term truth and reconciliation is being thrown around liberally, Nolan hopes his book instills understanding and compassion in others by shining a light on the racism and oppression experienced by Indigenous Peoples from the era of residential school system to now, and all of the intergenerational trauma that has come with it.

“I think the best thing about it is bringing truth to the people, so they have a bit of understanding of what people went through, and have a little bit more compassion for what they went through,” said Nolan. “When you see somebody down and out, there’s reasons, and assuming what people know about people, you can’t assume.

“Knowledge is the thing that’s going to get us out of here, so the more knowledge we have and the more compassion we have — and the more understanding we have — it’s going to be better for society, it’s going to be better for everyone. Not to have special treatment, just to have fair treatment.”